Event Date(s):

March 9, 2025 – September 20, 2026

Event Location: Museum of Contemporary Art (MOCA)

Los Angeles, CA

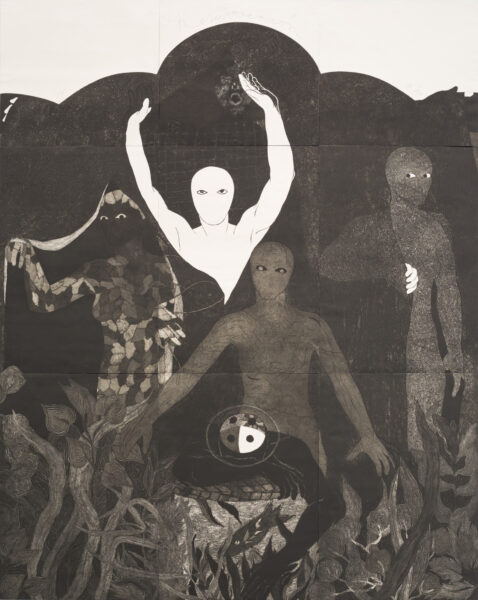

Diary of Flowers: Artists and their Worlds brings together over 80 artworks from MOCA’s renowned collection, demonstrating how artists create their own worlds through their art–building networks, circles, and mythologies. Embracing the boundaries between the personal and the social, public and private lives, as well as emotional and psychological states, works in the show privilege sites of creativity and the place of the imagination to conjure new worlds and possibilities. Friendship, love, and intimacy become important starting points for artistic expression. The exhibition features work in all media across different geographies, cultures, and periods, by artists including Belkis Ayón, Abraham Cruzvillegas, Mona Hatoum, Candice Lin, Annette Messeger, Wangechi Mutu, Lucas Samaras, Mohammed Sami, Tunga, and Haegue Yang, as well as a gallery dedicated to Nan Goldin.